Martin Crowe: The Man Cricket Never Caught Up With

Beyond USA March 3, 2016 admin 0

By Abhishek Mukherjee

Crowe had an impact as deep as any on the sport; he made a nation not used to success believe that they could challenge the best.

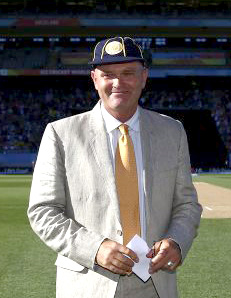

New Zealand most prolific cricketer, the late Martin Crowe. Photo: ICC

The world was prepared for it. We were aware that it was a matter of time. Almost a year to this date, we knew, as Australia took on New Zealand in the World Cup final, that the days of the greatest New Zealand batsman of all time were limited. And yet it came as a blow, for it is, will be, difficult to come to the fact that Martin Crowe is no more, for Crowe was no ordinary cricketer or individual. He had an impact as deep as any on the sport; he made a nation not used to success believe that they could challenge the best; and memories of his regal presence at the crease during his halcyon days will keep lingering in mind.

With the willow Martin Crowe was one of his kind, a batsman who could combine elegance with appetite for runs so effortlessly that you often wondered whether he was real. And then, there were the small matters of astute leadership that changed New Zealand cricket for good, and the fact that Crowe was one of the supreme analytical minds in the world of cricket.

Cricket telecast was not at its best in the 1980s, but Crowe’s prowess at the crease was impossible to miss. The arc of his bat, the footwork, the head position — everything told you he was one of those classicists, with an unmistakable touch of elegance they reserved only for a fortunate few. So good were his reflexes, so late did he often play the ball that you sometimes wondered whether he would ultimately play the ball or let it go despite the fact that it was aimed at the stumps. But then, so versatile was he around the ground that the ball invariably found the ropes, bisecting a pair of hapless fielders when they expected it to happen the least.

Indeed, Crowe was magical in his pomp, a delight for purists and fans and statisticians alike: few could, after all, followed the coaching manual so effortlessly, enthrall the crowd with breathtaking strokeplay, and yet emerge as the leader of batting charts for his country.

Crowe scored 5,444 runs from 77 Tests at 45.36. Before injuries began to mar his career, the average hovered around the 47-mark. Seven Tests before his retirement he averaged 47.98. It was clear, by then, that the body had stopped listening to the mind, but he had to go on, for he was the only major name in a line-up consisting of honest triers.

For us, used to Crowe’s dominance at the crease, it was heartbreaking to watch him struggle to get his timing going. Those last 7 Tests fetched him 214 runs at 19.45. He was not supposed to leave with a whimper.

Even after those last seven Tests, Crowe’s numbers remain fantastic, especially if you take into consideration that of New Zealand batsmen, only Stephen Fleming and Brendon McCullum have more runs even after two decades of his retirement, and none of them have batting averages remotely close. Crowe quit as New Zealand’s greatest batsman. Had a plague of injuries not led to a premature retirement at 33, you could have added the words “by a distance” without much deliberation.

He did dominate West Indies at their peak, with 544 runs from 7 Tests and 3 hundreds. He averaged 45.33 against the most fearsome pace quartet. When Richard Hadlee tore into Australia in 1985-86, Crowe played the support act with 188 at The Gabba (Australia got 179 in their first innings), and 71 and 42 not out at WACA.

Those were the two Tests New Zealand won on that tour. He topped the batting chart from either side. Australia proved to be his favourite hunting ground: from four tours and eight Tests he got 870 runs at 66.92 with 2 hundreds.

He was twenty-one when Somerset made him an offer. No, merely ‘made him an offer’ does not tell the story: Somerset hired him as replacement for Viv Richards, for back then he was already hailed as a childhood prodigy. He had failed in the Test series in England the previous season, but had impressed in the tour games and the World Cup (1983). In that first season he responded with 1,870 runs at 53.42 with 6 hundreds.

And when New Zealand co-hosted World Cup 1992, Crowe revealed his cards, one by one, in familiar circumstances: he put a brusque hitter at the top; he opened bowling with an off-spinner; and his attack revolved around a handful of medium-pacers who did little but bowl slow and straight.

One country after another succumbed on the small New Zealand grounds before they could come to terms with the stratagem: some tried to emulate, but by the time they realised what had hit them, Crowe’s men — a group of hardworking men with tremendous work ethic, a willingness to succeed, and the intent to adhere to a plan — had won seven matches on the trot. The juggernaut came to a halt only when a mercurial Pakistan side beat them twice in succession on their way to lift the World Cup.

Towering above them all was the genius himself: Crowe scored 456 runs at 114 and a strike rate of 91 before limping out of the tournament with a pulled hamstring during the semi-final. Even on that day he had seemed unstoppable, with an 83-ball 91.

It was also the first time the World Cup had a Man of the Series Award, and the choice was more than obvious. It broke hearts when Crowe limped during New Zealand’s lap of honour. It was evident how badly he wanted to win the World Cup.

New Zealand came agonizingly close again, in 2015, but it did not happen. The so-near-yet-so-far has been the story of his life, for his career-best came when he became the first (and remains the only one) batsman to be dismissed for 299 in Test cricket.

After retirement, Crowe kept providing cricket with insights. He invented Cricket Max, a 20-over format of cricket that preceded Twenty20 cricket, where the sides could bat 10 overs an innings. He suggested a knock-out Test championship that ICC toyed with for a while.

Crowe became a familiar voice behind the microphone and one of the most analytical cricket columnists. As early as in 2006 Crowe commented that “chuckers should be chucked out” of cricket. It took ICC almost a decade to listen to him.

Indeed, a man ahead of his times: way, way ahead. It may take cricket decades to catch up with his mind.

(Abhishek Mukherjee is the Chief Editor at CricketCountry and CricLife. He blogs here and can be followed on Twitter here.)

The above article is reproduced with permission from cricketcountry.com